The last week of trouble on the streets of British towns provides an interesting ‘field study’ of collective behaviour. While the media and politicians seek to simplify the argument, understanding is only reached by examining the full complexity of the situation. In seeking to remain as objective as possible, I’ll try to identify some diversity within these groups – starting with the ‘Rioters’:

The Destructors: These are those intent on destruction. Simply put, those who break the windows and light the fires. They are highly influential on those around them, perhaps due to infectious bravado and dynamism. They are likely to be within or supported by a close group of friends (e.g. gang structure) that encourages and respects this behaviour. They may be motivated by an underlying resentment for (and perhaps a lack of fear of) the police or their community in general, although this may not be the focus of their actions.

The Followers: These are those people bought onto the streets by sheer interest of what it happening in their neighbourhood. On seeing the behaviour of those mentioned above (perhaps viewed as fun, or exciting), twinned with a lack of police intervention, they will join in also, although without the same vigour pursued by The Destructors. They are likely to be more fearful of police action.

The Opportunists: These are those who did not get involved with the wanton destruction, rather they were attracted by the potential of looted items. They are united by a desire for material gain. This may be twinned with an underlying sentiment that they have not received as much in the way of these items as they perceive to be ‘fair’. This means that members of this group may be from any part of society, any person who feels that they deserve more. (Possible example: Laura Johnson)

The Observers: They were those just watching and not getting involved. Don’t underestimate the influence of hundreds of observers to make a riot look larger or more dangerous than it is.

In essence, it is too simple, too cack-handed to regard the ‘Rioters’ from one viewpoint. Within the population of people out on the streets during those nights is a great deal of diversity. This is important as it raises different questions as to how we deal with the underlying problems. For example, why were these ‘Opportunists’ (as I’ve have coined them) drawn out onto the streets? What can we do within our society, our society of superficiality and the culture of success attached to material wealth, to stop these people from acting this way again?

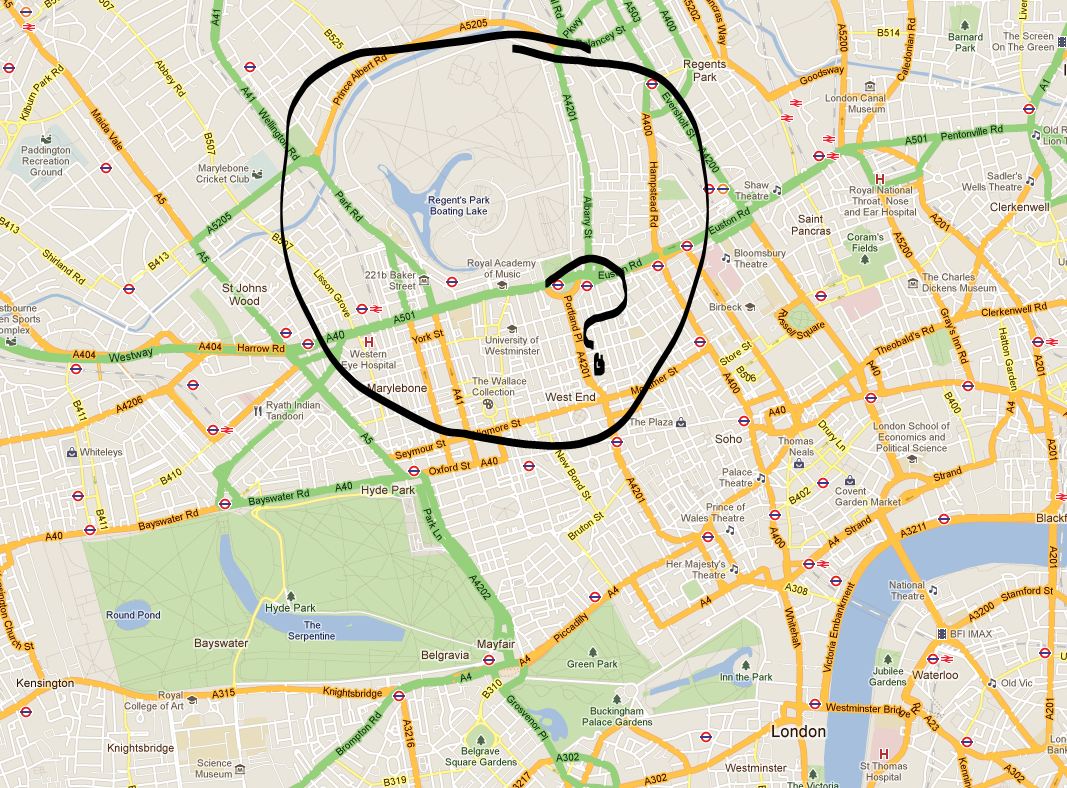

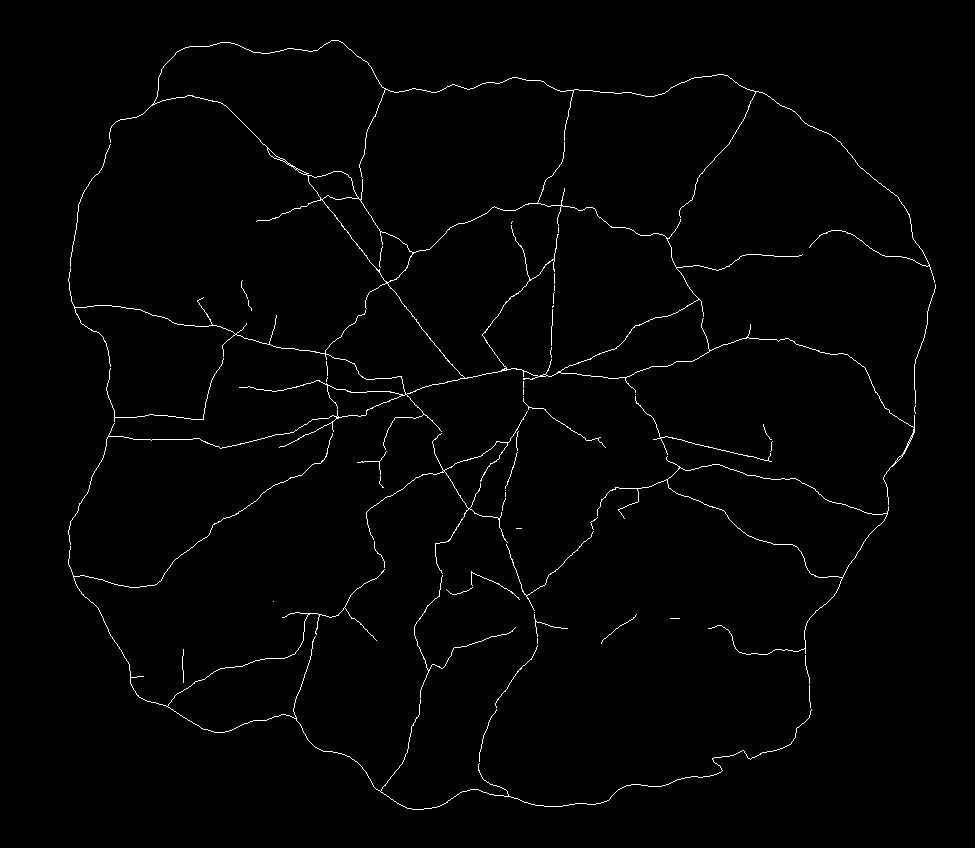

Furthermore, it is important the fully grasp the numbers of people we are talking about when it comes to addressing the scale of the issue. This is hard to get a grasp on, and while the news reports can provide some sense of this, they are only drawn to the worst examples of behaviour. However, I believe that, contrary to much opinion, there were only a small number of these so-called Destructors. Rather, the behaviour of these people (within gangs) was highly influential on those around them. Their own behaviour, and the resulting lack of action against them, encouraged the behaviour of those in other groups.

So when we did begin to see a crackdown by police, and arrests of hundreds of people, the rioting almost ceased straight away. This would support the idea of a far greater number of ‘Followers’, those keen to be involved in the ‘fun’ but not those who will start it – in some respects, those afflicted by the ‘Madness of Crowds’ (see former blog post). The Destructors, perhaps depleted in numbers and without the potential cover offered by the presence of many ‘Followers’, ‘Opportunists’ and ‘Observers’, simply stay at home.

The riots were a truly terrible event, but in seeking to understand what has happened we need to get a grasp of the full complexity of behaviour within the rioting populace. We are not talking about ‘feral youth’ or ‘people gone wild’, the situation is more nuanced and requires a careful form of analysis and politics that, I fear, it won’t receive.

At some point this week I will try to apply the same analysis to the actions of the wider population during this period.