It seems life and work is less than compatible with #content generation for this blog, so ‘why don’t I just’, I figure, ‘write a short piece about the research I have been doing in all this time’. I also figured this was a good idea, so here is the first in what I’m going to tentatively call a series of short descriptions of recent publications I have been involved with.

Disclaimer: I think transportation studies, at the risk of vastly overgeneralising matters, is a bit too interested with measuring ‘usual’ conditions. I can’t blame people who do that sort of research – we are still suffering with strained transportation systems, congested, crowded, and polluted, that are damaging to economies, to health, and wellbeing. But in focusing too much on ‘usual’ patterns, we miss the effect of disruption and rapid change, and once we start considering those, maybe there is no ‘usual’ after all.

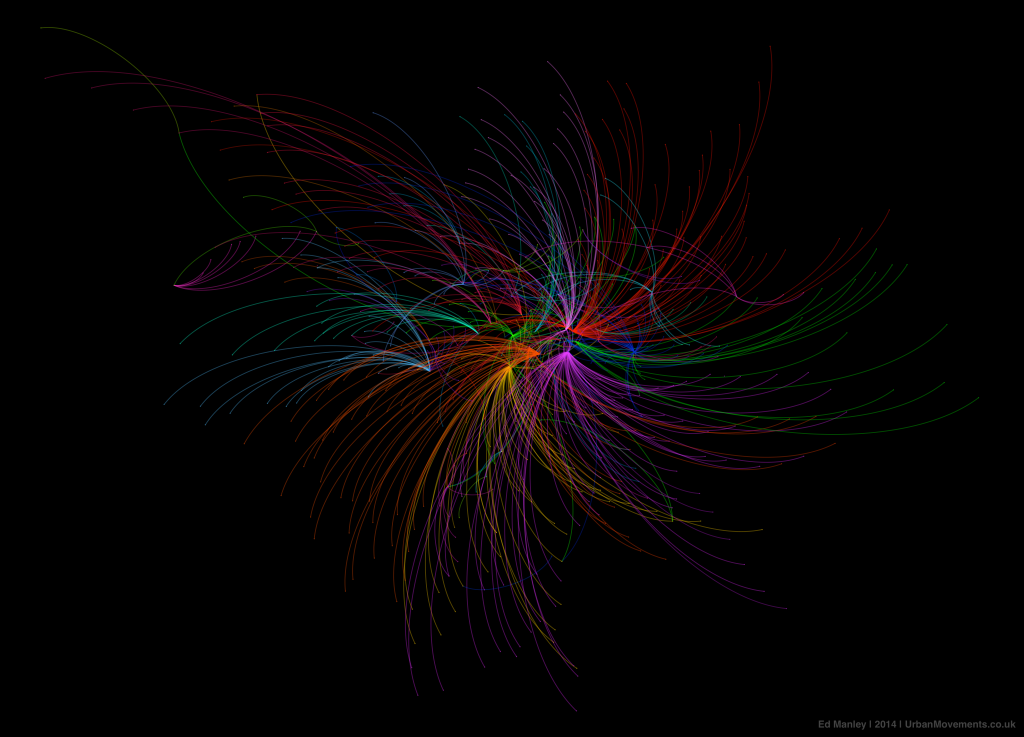

This particular piece of research focused on the spatial and temporal appearance of ‘usual’ and ‘unusual’ travel behaviour on the London public transport system. Through a long-term collaboration with Transport for London we analysed around 1 billion Oyster Card transactions, and constructed patterns of ‘usual’ travel behaviour at the (anonymous) individual scale. These ‘usual’ patterns of behaviour are constructed through a simple DBSCAN clustering of data points over space and time, with these clusters indicative of regular activity. We make a simple assumption that if a person appears at this space and time on a regular basis (as defined by the clustering algorithm), then that is a ‘usual’ activity for that individual. Most importantly, perhaps, the classification of ‘usual’ activity at an individual scale, allows us to identify spatial and temporal occurrence of ‘unusual’ activity. This differentiation enables us to understand travel behaviour from a different point of view.

There are various findings from this work, and these can be better explored in the paper itself, but here are a few highlights.

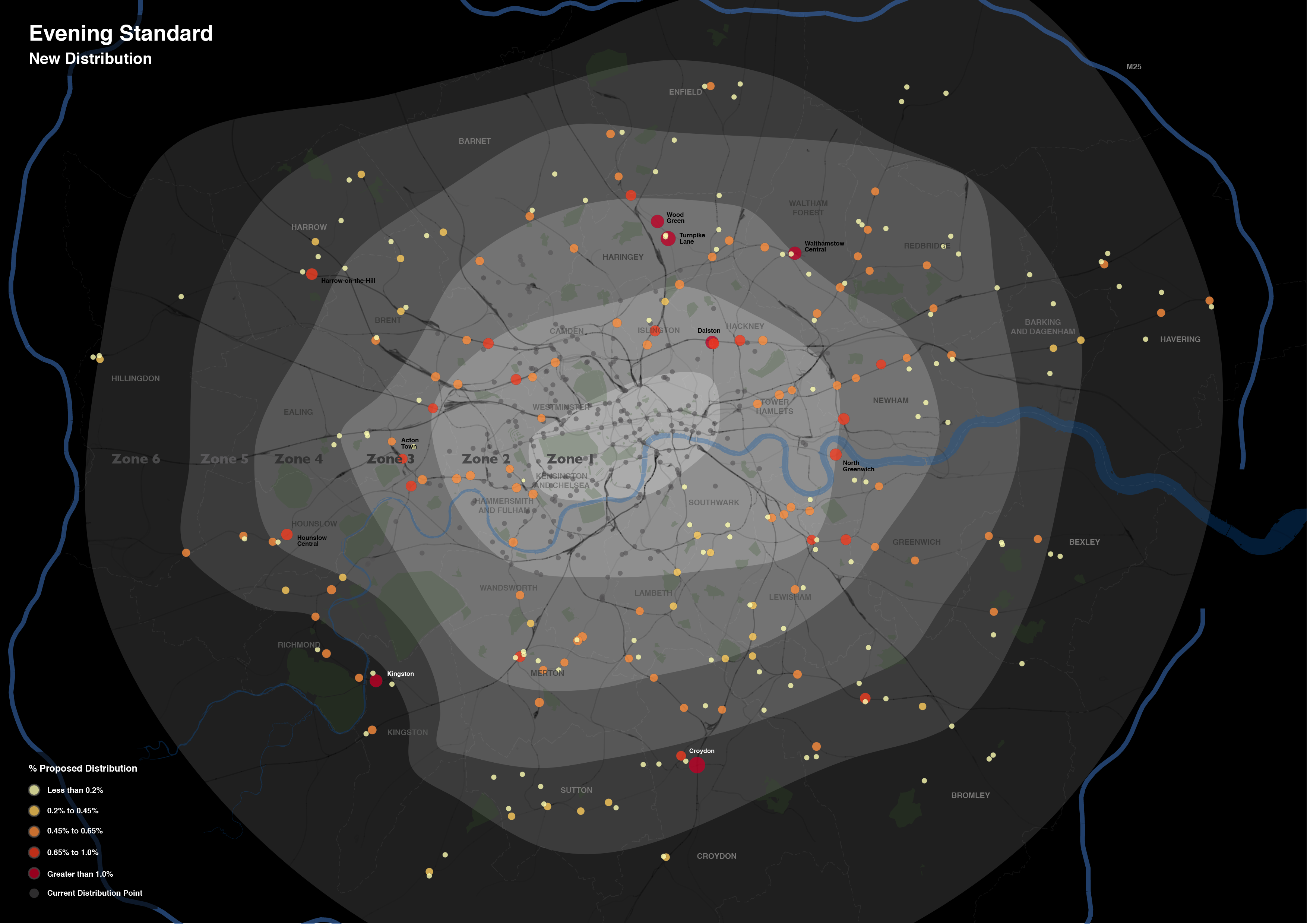

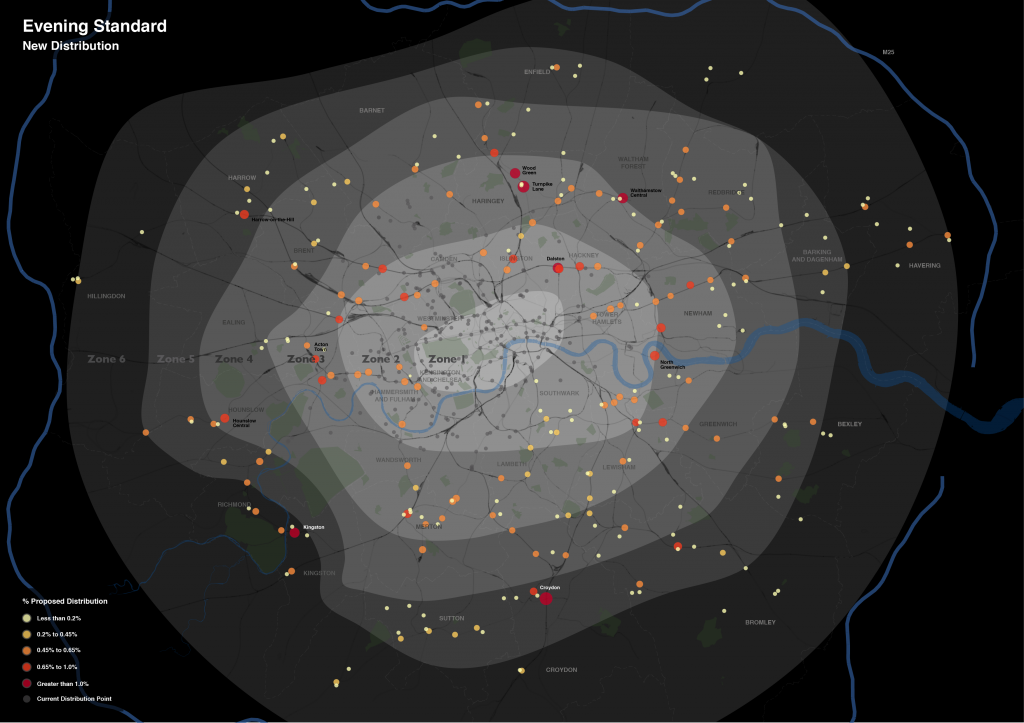

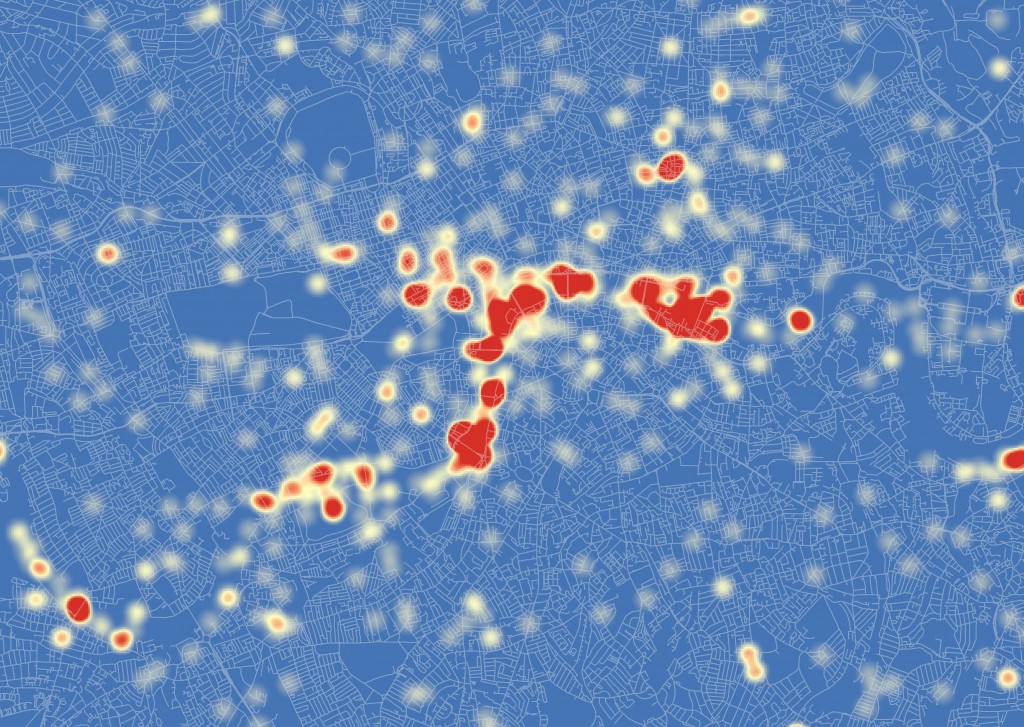

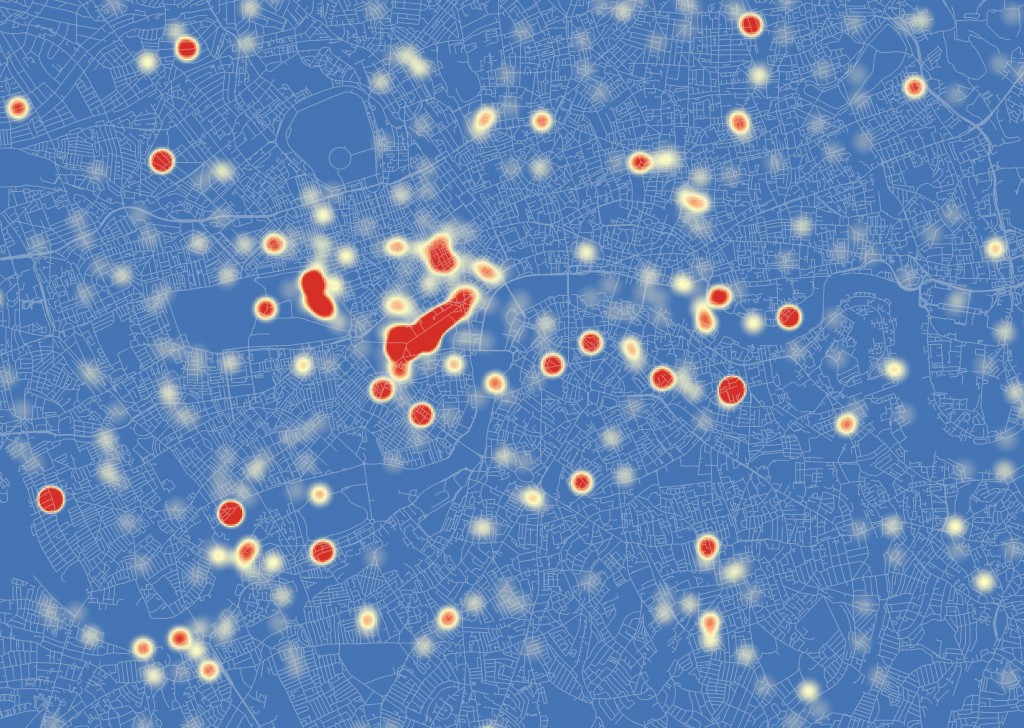

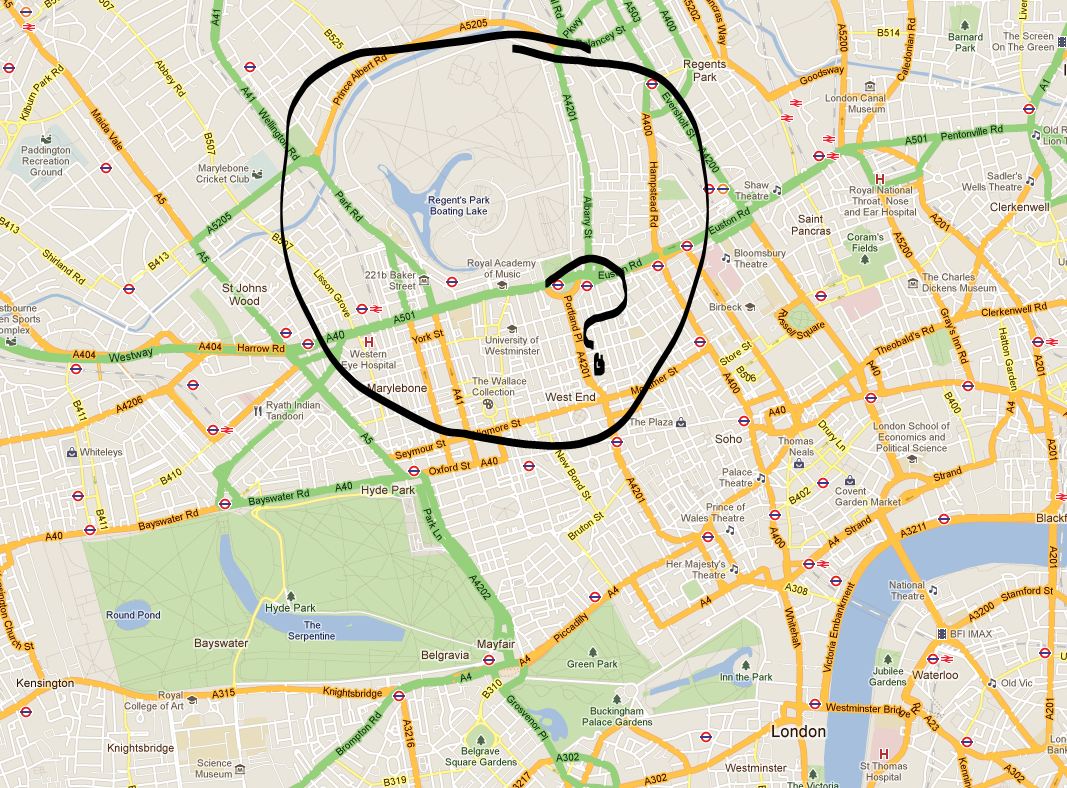

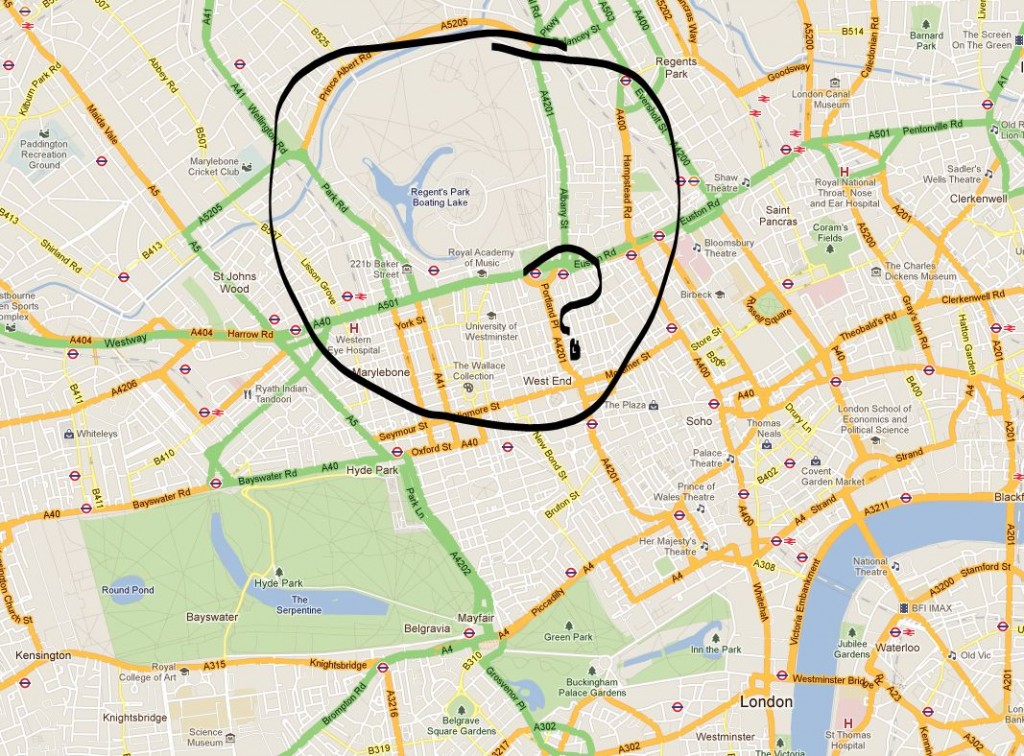

For me the most interesting snapshot is the spatial variation in ‘usual’ Underground journeys. The maps show us proportions of ‘usual’ journeys occurring in each Underground station, relative to ‘unusual’ journeys. And, in fact, we see quite a lot of variation in this behaviour. Commuter belt zones in outer London, such as Sudbury and Roding Valley, demonstrate high proportions (55% to 75%) of regular journeys. This suggests that people are more regularly undertaking journeys to work from these locations, as opposed to other activity, and perhaps work in industries with strong ties to defined working hours. These areas, I would expect, have fewer attractions that lead to ad hoc journeys to be conducted there. On the opposite end of the spectrum are placed like Covent Garden, which demonstrate low levels (below 30%) of regular activity. This is in part due to these areas being full of tourist attractions, restaurants, and other reasons for trips to be conducted there at a variety of times of day. Also ranking low at the airports, Heathrow and City. This is no surprise, relatively few people work regularly at this locations, but provides us with some validation of the approach used here.

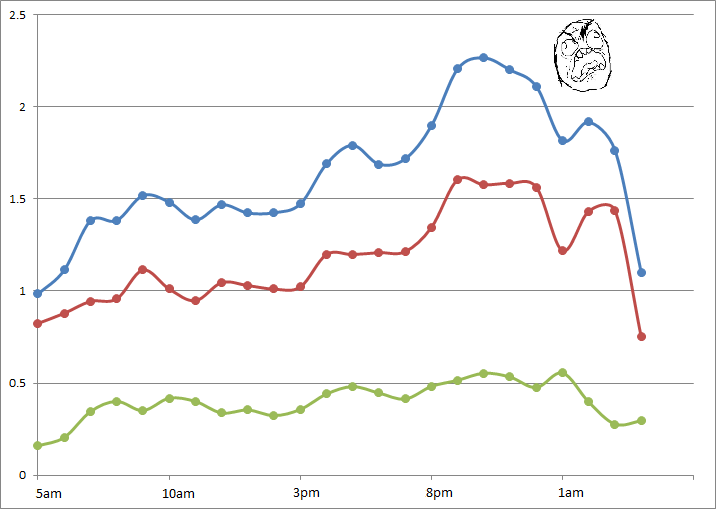

In the paper, we also explore temporal variation by different modes, exposing some quite diverse uses of different travel modes. As expected, each mode shows higher regularity during peak times, however, the extent to which ‘unusual’ travel fills that gap varies by mode. On the bus, for example, regular journeys are observed at a steady rate (around 75%) throughout the day, whereas on the Underground we see a drop to below 40% during the same period, as shown in the chart below.

There is an extent to which this work exposes some of the trends we already sort of understood. But I think this sort of analysis goes much further than this, and allows for significantly more nuance in the way we manage transportation systems. If we’re able to better understand how people are using the transportation systems at finer spatial and temporal detail, then we can potentially develop policies and management strategies that match that granularity. Through this deeper understanding, our transportation systems can build in more depth and resilience to disruption and change.

The paper was published in Transportation in 2018 (it was, err, actually completed quite a long time before that…), and is available open access from this link if you want to find out more.