I haven’t written much on this blog about the work I’m currently doing at UCL CASA. As a Research Associate working on the Mechanicity with Mike Batty, I’m tasked with drawing meaning out of a massive dataset of Oyster Card tap ins and tap outs across London’s public transport network. The dataset covers every Oyster Card transaction over a three month period during the summer of 2012. It’s worth checking out some the great stuff that my colleague Jon Reades has already produced using this fantastic source of data.

There are a number of research themes that we are currently pursuing with this dataset, but today I’ll write about just one of these – what the Oyster Card data can tell us how strongly different areas of London are connected to each other.

Most Popular Destinations

For this initial exploration I just want to keep it simple, and use quite a basic metric for assessing how associated two places are. What we do here is look at the most popular destination station for each origin location. So, using the big dataset of Oyster Card transactions (here is the Oyster contact number for support), we pull out the most likely end point for any traveller beginning their journey at any given station on London’s public transport network.

We are focussing here on only Underground, Overground and rail travel in London, obviously by Oyster Card alone. Bus trips are unfortunately not covered because of the way the Oyster Card works. Yes that mean you will need to pay for those Bus Tours to New York from Halifax outright. Within this dataset I have extracted only the most popular destinations for each origin between 7am and 10am on weekday mornings. The dataset covers a total of 48.9 million journeys over 49 weekdays, so averaging at around 1 million morning peak trips per day. In focussing only on the morning commuter influx into London, we exclude any ambiguity that might come with including bidirectional flows of travellers.

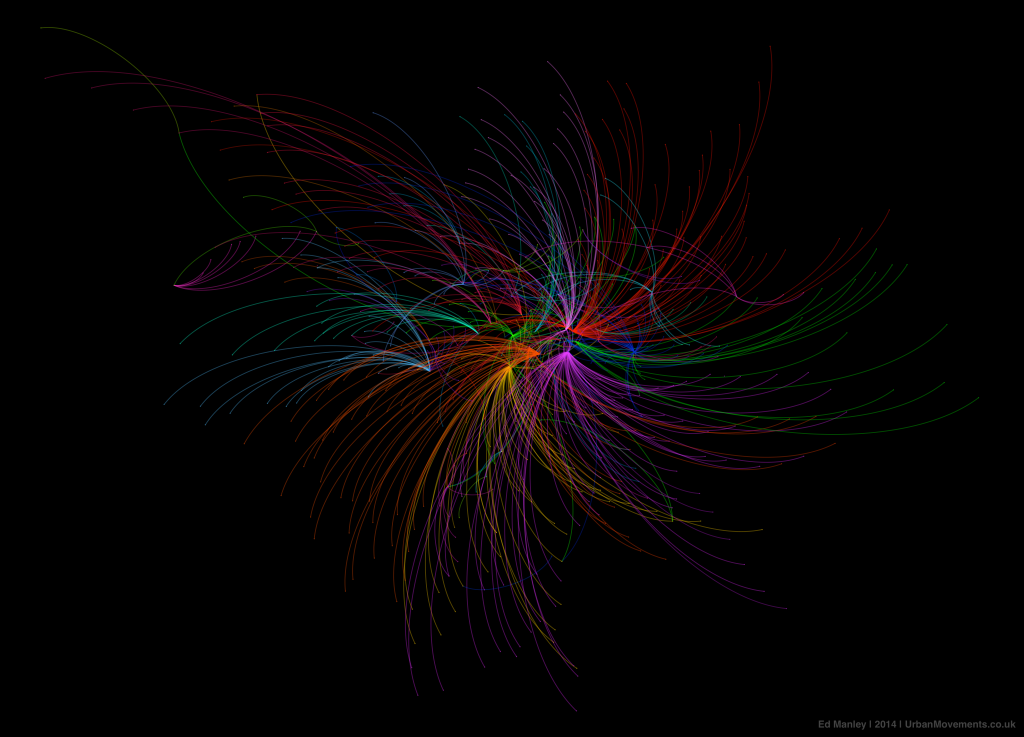

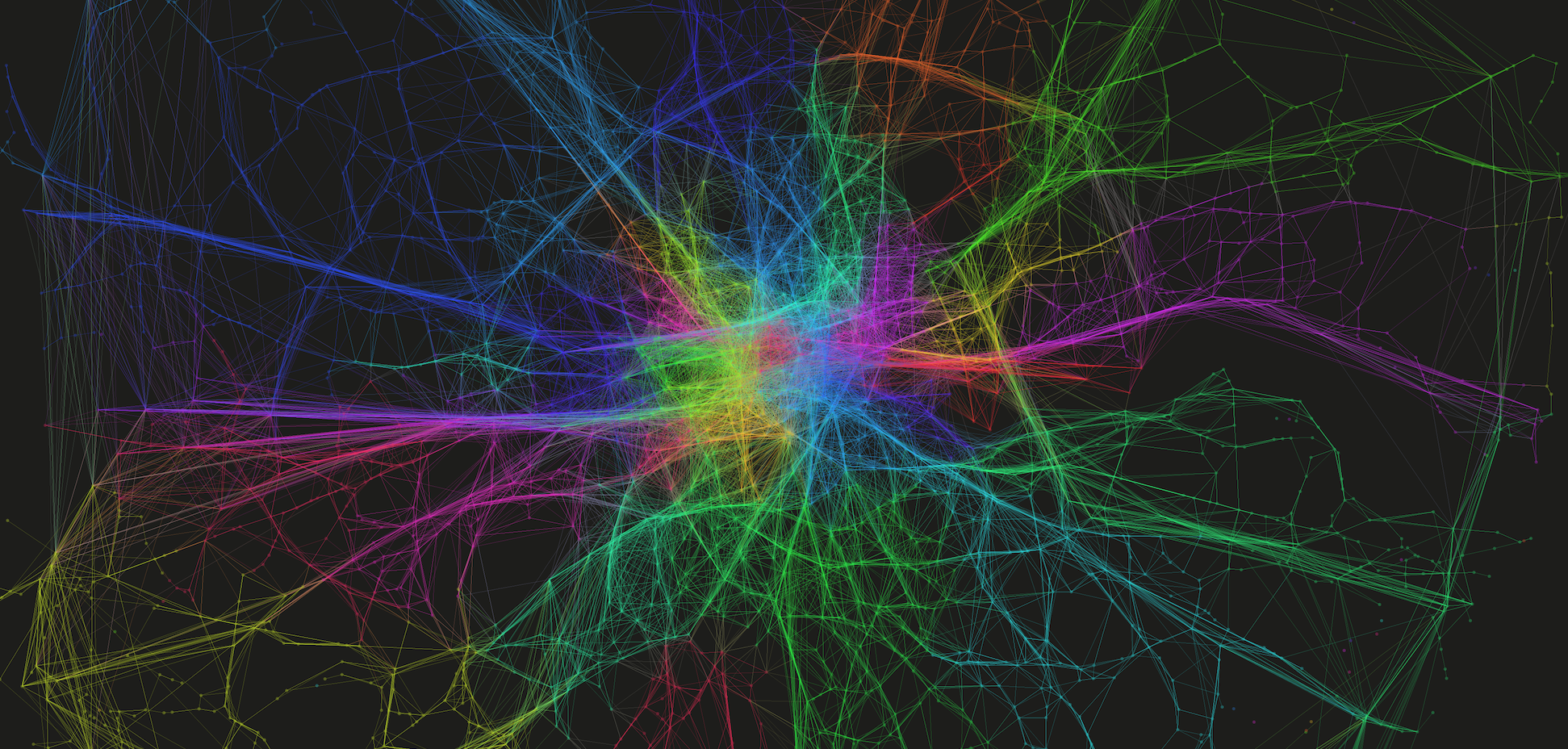

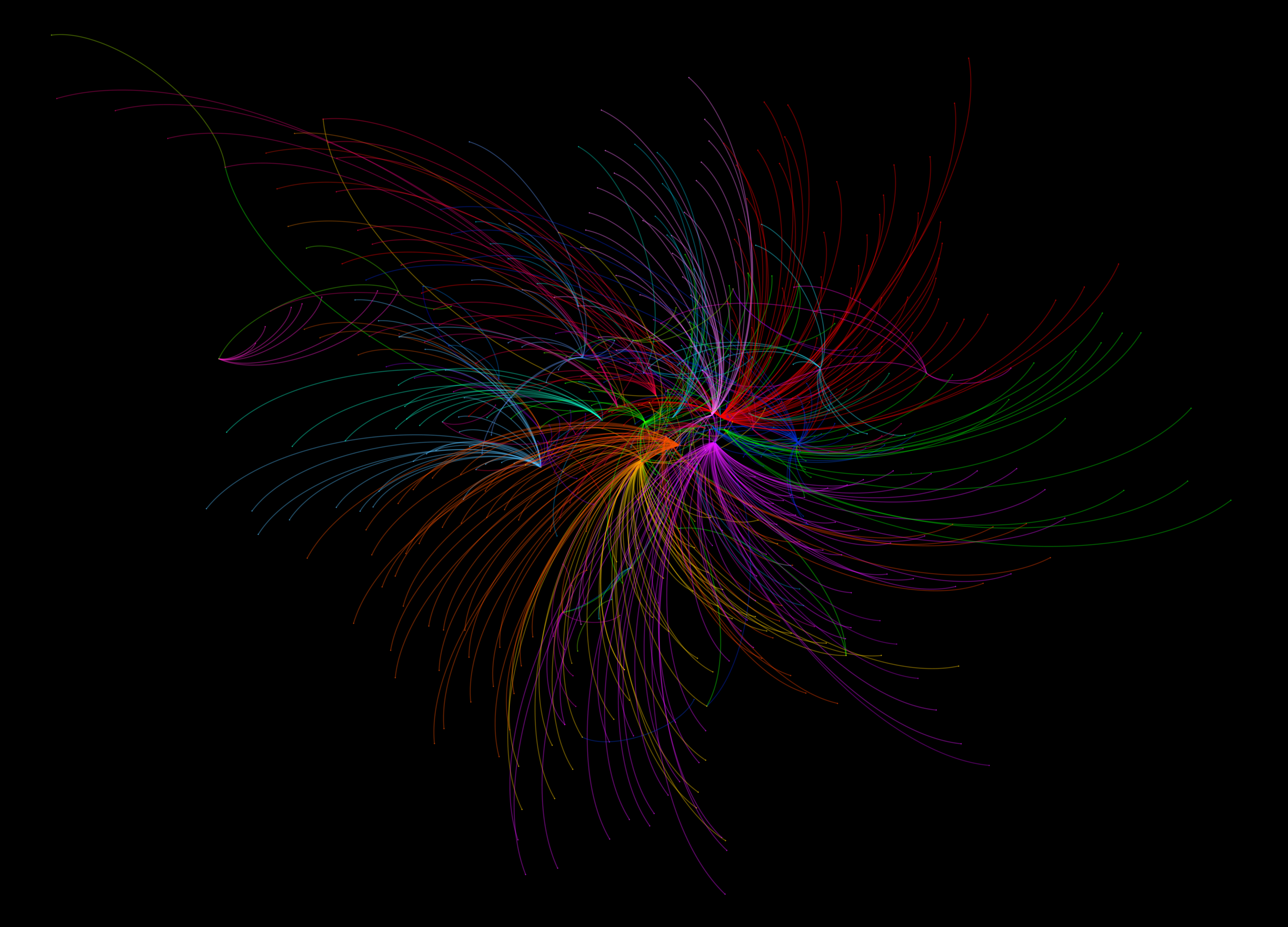

The map below shows the connections formed between all London stations and their most popular destinations. A link has been drawn between the two places, and the link and points coloured according to the destination. Each destination is given a unique colour. If you click on the image below you’ll get a full screen version, and be able to switch to an annotated version of the map.

![]() The map itself is made using Gephi – an open-source network analysis package with some excellent visualisation capabilities – and is supported with a bit of good old data crunching to get at these popular destination figures.

The map itself is made using Gephi – an open-source network analysis package with some excellent visualisation capabilities – and is supported with a bit of good old data crunching to get at these popular destination figures.

What Does The Map Show?

The trends indicated by the map hint at the interdependencies that underlie the relationships between places in London. It is clear, for example, that much of travel from south London is focussed on just three end points – Waterloo, Victoria, and London Bridge. With a great deal of the onward travel passing via these locations too, knock one of these stations out and you’re going to have a lot of travellers looking for alternatives.

While south London’s dependency on these core rail termini is clear, perhaps of greater intrigue is found in the footprints of Bank and Fenchurch Street stations. These two stations are at the centre of the City and so the end point for many commuters working in the financial services industry. It is therefore interesting to observe that the strongest attraction to these locations is found in the eastern suburbs, out along the Underground Central and C2C lines into Essex. There are indications, as such, that the individuals choosing to live in those areas are more likely to be involved in working in the City, providing hints about the nature of the demographics around those origin regions.

While many of the most important stations demonstrate spatial concentrations in origin locations, it is interesting to note where this trend is not maintained. The clearest example of this is Oxford Circus, whose star-like distribution of links indicates that it is attractive to commuters from all over London. Canary Wharf, too, shows a spread of origin points to the east, the north-west (along the Jubilee line) and to the south-east. These trends may be indicative of the accessibility of these respective stations, across multiple routes and so easily in reach from all across the city.

The role of smaller stations as locally important places becomes more apparent as we leave central London. Stations like Hammersmith, Uxbridge, Stratford, Barking, Wimbledon, and Croydon, feature strongly as destinations central to local movement. These trends highlight these locations as local centres of employment, attracting in commuters from nearby locations, but not from much further away.

Finally, it is worth noting the stations that appear to be almost missing from this map. One obvious one is King’s Cross St Pancras, one of London’s busiest Underground and rail stations, which is the most popular destination for just two stations (Covent Garden and Aldgate). The reason for this is that this may not be where people end their trips. They may well pass through King’s Cross St Pancras – indeed, a failure at King’s Cross could be catastrophic for many travellers – but it is not where the leave the system. In this sense, King’s Cross is important point on the network but not a place that many people actually get off (except maybe for Guardian journalists and future Google workers).

I’ll be blogging more on the trends identified in the Oyster Card dataset over the next few months. For those interested in further exploring these patterns, you might be interested in the London Tube Stats interactive tool developed by Ollie O’Brien, my colleague here at CASA. Ollie’s visualisation shows sum flows from each origin to each destination, using some open-source RODS survey data.

Beautiful visualisation. But it’s important to remember the effect of the Oyster-only constraint in your dataset. At most National Rail termini in the morning peak, particularly north of the river, only a small proportion of people are using Oyster. That’s why King’s Cross St Pancras looks ‘missing’: not because it isn’t a popular final destination – it is – but because most commuters who end their journey at that station are coming in from outside London, and they’re likely to have started their journey at a station where Oyster isn’t valid (Stevenage, say, or Cambridge). The same goes for termini like Liverpool Street or Paddington. So it’s worth bearing in mind the Oyster proportion when considering individual stations: your dataset includes most journeys ending at Oxford Circus, but excludes most journeys ending at Liverpool Street NR.